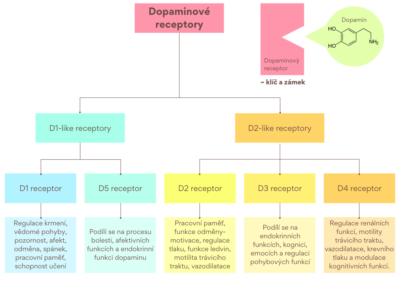

In today’s world, dopamine, belonging to the group of so-called happiness hormones, is mainly associated with reward and the subsequent experience of joy and euphoria. However, dopamine also plays a crucial role in other physiological processes and behaviors. It is a neurotransmitter that enables communication between neurons. Its optimal level supports cognitive performance, motor functions, increases motivation, improves mood, and regulates wakefulness (see Picture. 1). All these processes are also linked to circadian rhythms. In this article, you will learn how the desynchronization of circadian rhythms (CR) is related to diseases that are specifically associated with dopamine imbalance.

Circadian rhythms are biological processes that occur in the body in approximately a 24-hour cycle. These biological processes are regulated at the molecular level by so-called clock genes and proteins. A variety of molecules help maintain the proper rhythmicity of these genes, and one of them is dopamine. Its circadian activity has been proven in five areas of the brain, including the retina and the hypothalamus, which houses the so-called suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN). The SCN serves as the primary pacemaker of circadian rhythms, ensuring the correct timing of biological clocks in all other areas.

Picture. 1: Dopamine is a hormone and neurotransmitter that is primarily released by nerve cells and binds to specific receptors (D1, D2, D3, D4, or D5) of other cells, thereby enabling the transmission of impulses from neurons to other cells. Depending on the type of receptor and the type of cell receiving the signal, dopamine plays a role in several different physiological functions. The diagram has been adapted from source: 1).

Circadian rhythm disorders have a clinical connection with mood disorders. This link between CR and behavior can also be observed in various neurodegenerative diseases (ADHD, autism, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease). For example, in Parkinson’s disease, the degeneration of neurons, or the death of brain cells, specifically dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain, leads to a decreased ability to release dopamine. Thanks to extensive research, we now know that in Parkinson’s disease, in addition to motor impairments, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, and other symptoms are also observed.

CR is connected to dopamine regulation through two key proteins (REV-ERBα and CLOCK), which are essential components of the molecular feedback loop that forms the core machinery of the entire circadian rhythm. REV-ERBα inhibits the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, which is crucial for dopamine synthesis. A mutation in the CLOCK gene, which encodes the CLOCK protein, causes manic episodes by increasing dopamine levels in the midbrain. In disorders where low dopamine levels are observed, such as ADHD, disruptions in the levels of BMAL1 and PER2 proteins have been demonstrated.

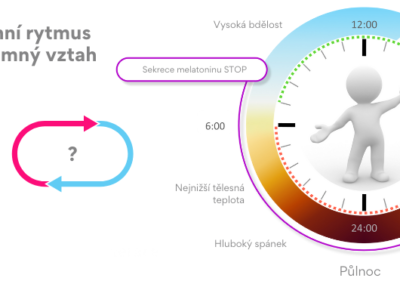

Based on these findings, it can be assumed that circadian rhythm desynchronization leads to the desynchronization of clock genes, with disturbances in the levels of proteins derived from these genes observed in diseases where dopamine balance is also disrupted. However, if we look at the reverse relationship—how dopamine affects circadian rhythms—we can take the example of the retina. Dopamine release in the retina enables proper adaptation to light, which is the main Zeitgeber ~ synchronizer of circadian rhythm, and the transmission of information from the external environment to the SCN. Thus, a reduced level of dopamine in the retina may impair light adaptation and consequently disrupt circadian rhythms.

In conclusion, the relationship between dopamine and circadian rhythms appears to be bidirectional, meaning that the circadian rhythm regulates dopamine while dopamine also regulates the circadian rhythm. From this perspective, it is truly important to follow the basic principles of light hygiene: exposing oneself to sufficient and high-quality light during the day, and if sunlight is not available, at least using electric light with a spectrum as close to natural sunlight as possible, while minimizing light exposure in the evening and at night.

Mgr. Tereza Ulrichová, Spectrasol

References:

1) R. Kant, M. Meena, and M. Pathania, ‘Dopamine: a modulator of circadian rhythms/biological clock’, International Journal of Advances in Medicine, vol. 8, p. 316, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.18203/2349-3933.ijam20210285.

2) J. Kim, S. Jang, H. K. Choe, S. Chung, G. H. Son, a K. Kim, „Implications of Circadian Rhythm in Dopamine and Mood Regulation”, Molecules and Cells, roč. 40, č. 7, s. 450–456, july. 2017, doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.0065.

3) K. S. Korshunov, L. J. Blakemore, a P. Q. Trombley, „Dopamine: A Modulator of Circadian Rhythms in the Central Nervous System”, Front Cell Neurosci, roč. 11, s. 91, dub. 2017, doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00091.

4) N. Bauer, D. Liu, T. Nguyen, a B. Wang, „Unraveling theInterplay of Dopamine, Carbon Monoxide, andHeme Oxygenase in Neuromodulation andCognition”, ACS Chem. Neurosci., roč. 15, č. 3, s. 400–407, february. 2024, doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00742.

5) R. M. Grippo a A. D. Güler, „Dopamine Signaling in Circadian Photoentrainment: Consequences of Desynchrony”, Yale J Biol Med, roč. 92, č. 2, s. 271–281, june. 2019.

Translated using AI