In recent years, the term “human centric lighting” has become known to architects, designers, lighting manufacturers, and customers in connection with lighting. Human centric lighting (HCL) or “integrative lighting” is, according to the ISO/CIE definition, a lighting principle that considers not only the visual but also the non-visual effects of light on humans and positively affects their physiological and mental needs. It was designed to mimic natural daylight, which changes its intensity, spectral composition, and correlated color temperature (CCT) throughout the day and evening. Unfortunately, HCL is largely associated with LED lights that only change their color (CCT) during the day, and with “tunable white” bulbs. However, this article explains why CCT is not the only parameter to focus on when designing interior lighting in relation to the biological effects of light.

What is crucial when designing interior lighting

When designing lighting, it is important to focus on four basic parameters of light, following nature’s example: a) timing and duration of light exposure, b) spectral power distribution (SPD) of the given light source – for simplification, further referred to as spectral course or composition, c) light intensity in radiometric and photometric units (illuminance, irradiance, luminous flux…), and d) spatial distribution in the room (see fig. 1). By manipulating these parameters, one can influence not only the visual effects – visual perception, visual experience, comfort, and subjective feeling of light – but also the non-visual (NIF, non-image forming) effects of vision, which are becoming key in relation to health, specifically to circadian rhythm, neuroendocrine responses (hormonal response regulated by the central nervous system), and human behavior (alertness, cognitive performance, vitality, mood…). Visual effects are primarily mediated by rods and cones, while NIF effects are mediated by intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs). However, these four variables do not contribute equally to NIF effects, and therefore some of them are not nearly as good indicators of so-called biological effectiveness of light.

Fig. 1: The four most important parameters to consider when designing interior lighting: a) timing and duration of light exposure, b) spectral power distribution (SPD) of the light source, c) light intensity, d) spatial distribution of light. Information in the image was taken from the study (2)

Biological effectiveness of light – NIF

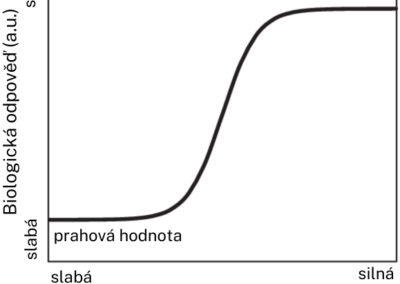

To quantify the biological effectiveness of light, the following two approaches are most commonly used today. The first is the CIE S026 method, based on the spectral response of photopigments in rods, cones, and ipRGCs. Therefore, the variable α-opic equivalent daylight illuminance (EDI) was introduced, but for biological effectiveness, the response from ipRGCs is crucial, and thus mainly the variable melanopic equivalent daylight illuminance (mel-EDI) and possibly equivalent melanopic lux (EML); these variables are derived from the melanopic daylight efficacy ratio (mel-DER). This approach is currently the only internationally approved standard for characterizing the biological effects of light. While it is consistent for calculating the response of photoreceptors to a light signal, it does not consider what happens to the transmitted signal at the level beyond the retina. For example, if mel-EDI increases by 50%, we cannot say with certainty whether melatonin expression will decrease by 50%. Biological responses to light tend to have a sigmoid dependence expressed in a log-linear diagram, see fig. 2. The second approach deals with the suppression of melatonin synthesis at night using the circadian stimulus (CS) metric. However, melatonin suppression may not sufficiently predict changes in other non-visual effects of light (increased alertness, phase shift of circadian rhythm, etc.). Neither of these approaches is entirely perfect, and in the future, it will be necessary to find a quantification method that reflects all non-visual effects of light.

Fig. 2: Sigmoid dependence of biological response on light intensity. The horizontal axis shows the amount of light in arbitrary units on a logarithmic scale, e.g., irradiance (W), illuminance (lux), mel-EDI (lux), or dose (J/m2). The vertical axis represents the biological response to light scaled linearly: suppression of melatonin synthesis, phase shift, subjective sleepiness, etc. At very low and very high light levels (e.g., dose), there is only a negligible difference in biological response; the light stimulus is either below the threshold value or, conversely, high near saturation, so-called saturation. The diagram was taken from the study (2).

People who spend most of their time indoors generally have a reduced contrast between day and night perception due to decreased daytime illuminance and increased nighttime illuminance compared to our ancestors and people who spend most of their time outside in daylight. Therefore, the goal of HCL should be to create an environment where the contrast between day and night is maintained. However, the light spectrum (SPD) itself is also crucial.

Human centric lighting (tunable white) and its challenges

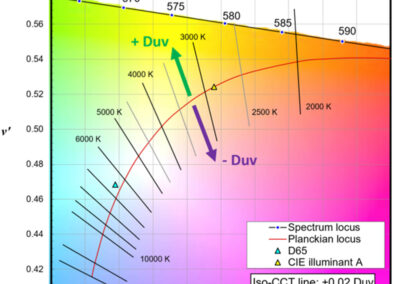

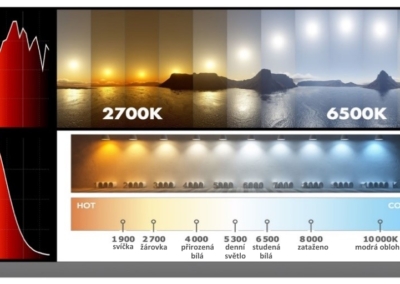

Thanks to revolutionary findings in chronobiology, we are in a new era of HCL. Until now, changes in correlated color temperature (CCT) and possibly light intensity occurred only in the active part of the day. CCT is easily accessible information found in product specifications, describing how we perceive the color tone of light, and should be applied only to light sources that are formally white. We usually perceive light with higher CCT as cooler light, while light with lower CCT is perceived as warmer light. However, CCT does not tell us how the SPD of the given light source looks. It is a one-dimensional reduction of SPD that alone cannot reliably predict the biological effectiveness and health impacts of light on humans. Many scientific studies (5–8) have compared the effects of light with different CCTs on cognitive performance, subjective satisfaction, mood, and sleepiness of office workers or students in schools, even though the light sources lacked emission in the melanopic cyan wavelength range. A systematic review (9) additionally summarizes several other studies whose results are diverse and lack consistency. The problem is that light fixtures with different spectral compositions can have identical CCT based on its definition, as seen in the chromaticity diagram (colorimetry triangle) in fig. 3. This may be why study results are inconsistent. Providing SPD, or CCT in combination with Duv, is a solution to achieve the replicability of studies and meta-analyses with the transfer of conclusions into practice. Duv is the distance of the chromaticity coordinates of a given light source from the nearest point on the Planckian locus, see fig. 3.

Fig. 3: Excerpt from the CIE 1976 chromaticity diagram (u’,v’). Lines represent constant CCT values. The Planckian locus, red curve, represents the chromaticity coordinates of blackbody radiation at various temperatures. Duv is the distance of the chromaticity coordinates of a given light source from the nearest point on the Planckian locus. The image was taken from the study (4).

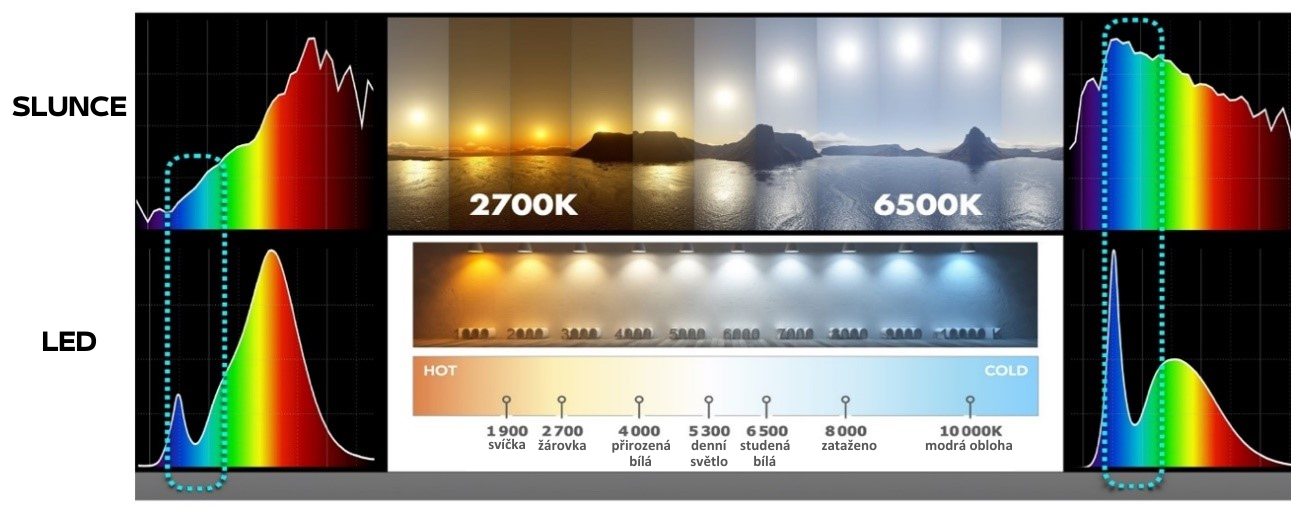

In conclusion, correlated color temperature (CCT) is a measure of the visual perception of light color and should immediately raise doubts about whether it can be related to non-visual effects. Conversely, a light fixture with an optimally designed spectral course combined with a suitable illuminance value at the right time is crucial for evaluating biological effectiveness. During the day, the organism (except for nocturnal creatures) needs bright white light with a balanced spectral course, including short cyan wavelengths (ideally those corresponding to the absorption ≈ action spectrum of melanopsin, with a peak around 480 nm). Such light provides the necessary biological signal for the human organism compared to dimmed light or light with a dip in the melanopic region used at the same time. Sunlight and LED light sources can have the same CCT value but completely different SPD (see fig. 4), and thus completely different impacts on the organism. Differences are particularly noticeable in the cyan and red regions of the spectrum. Lighting that supports the non-visual effects of vision in places where people should be active, whether they perform cognitive or physical tasks (i.e., where they do not relax or sleep), can be static without changing the spectral composition and intensity throughout the day if the parameters are correctly set to the daily optimum of natural sunlight (illuminance, CCT, and primarily SPD).

Fig. 4: HCL based on tunable white light sources and a comparison of the spectral course of sunlight and LED light sources with CCT: a) 2700 K (left), b) 6500 K (right).

Full-spectrum sources mimic natural sunlight and are an ideal solution for interior lighting during daytime activities in the context of the new HCL concept to maintain human health and support work vitality and user mood. This is especially important because all the effects of light on living organisms have not yet been explored, and any deviations in artificial lighting compared to natural light in interiors are not desirable for long-term user stay to avoid potential yet unexplored or more closely studied negative impacts. Among other things, this also offers significant potential for improving activities and resulting organizational outcomes

Mgr. Tereza Ulrichová, Spectrasol

Studies from which the article is based:

- K. Houser a T. Esposito, „Human-Centric Lighting: Foundational Considerations and a Five-Step Design Process“, Frontiers in Neurology, roč. 12, s. 630553, led. 2021, doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.630553.

- K. Houser, P. Boyce, J. Zeitzer, a M. Herf, „Human-centric lighting: Myth, magic or metaphor?“, Lighting Research & Technology, roč. 53, č. 2, s. 97–118, dub. 2021, doi: 10.1177/1477153520958448.

- T. Esposito a K. Houser, „Correlated color temperature is not a suitable proxy for the biological potency of light“, Sci Rep, roč. 12, č. 1, s. 20223, lis. 2022, doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-21755-7.

- D. Durmus, „Correlated color temperature: Use and limitations“, Lighting Research & Technology, roč. 54, č. 4, s. 363–375, čer. 2022, doi: 10.1177/14771535211034330.

- R. Lasauskaite a C. Cajochen, „Influence of lighting color temperature on effort-related cardiac response“, Biological Psychology, roč. 132, s. 64–70, úno. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.11.005.

- Y. Yuan, G. Li, H. Ren, a W. Chen, „Effect of Light on Cognitive Function During a Stroop Task Using Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy“, Phenomics, roč. 1, č. 2, s. 54–61, dub. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s43657-021-00010-5.

- W. Luo, R. Kramer, M. Kompier, K. Smolders, Y. de Kort, a W. van Marken Lichtenbelt, „Effects of correlated color temperature of light on thermal comfort, thermophysiology and cognitive performance“, Building and Environment, roč. 231, s. 109944, bře. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109944.

- R. Lasauskaite, M. Richter, a C. Cajochen, „Lighting color temperature impacts effort-related cardiovascular response to an auditory short-term memory task“, Journal of Environmental Psychology, roč. 87, s. 101976, kvě. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101976.

- C. Wang et al., „How indoor environmental quality affects occupants’ cognitive functions: A systematic review“, Building and Environment, roč. 193, s. 107647, dub. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107647.

Translated using AI